SQL Fuzzy Match Guide: How Fuzzy Matching Works in SQL (Updated for 2025)

Introduction

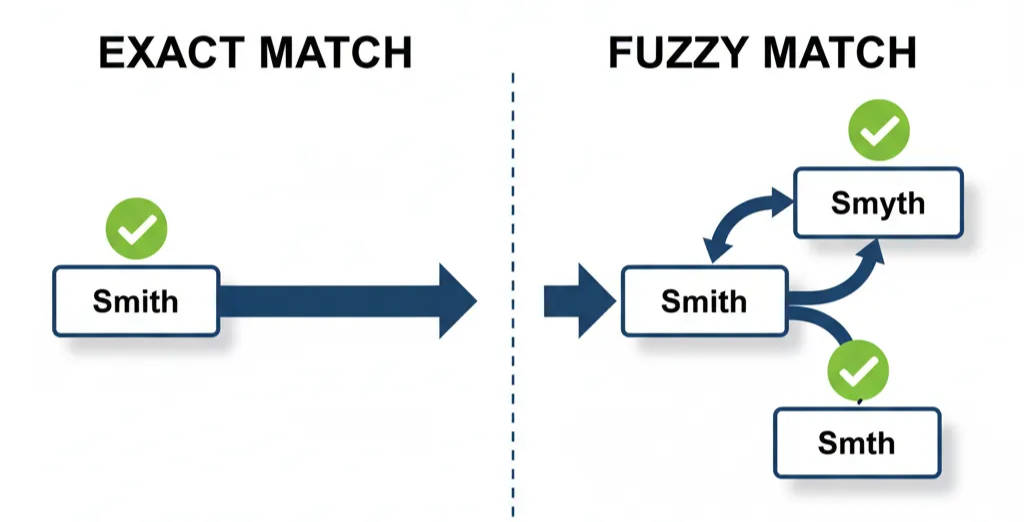

Fuzzy matching in SQL is a technique used to find approximate matches for a given string, rather than exact ones. Unlike standard SQL queries that require an identical character-for-character match, fuzzy matching allows for slight variations, such as typos, misspellings, or minor differences in formatting. It’s often used when dealing with messy or inconsistent data. For example, a search for “Smith” might also return “Smyth” or “Smth.” This is particularly useful for searching databases where data entry errors are common.

This skill is especially crucial for Data Engineering and Data Science roles, where data quality and reliability is vital for downstream tasks.

What are the uses of SQL Fuzzy Matching?

Fuzzy matching shines in situations where data is messy, inconsistent, or prone to human error, making it vital to Data Engineering and Data Science interviews. In relational databases, especially when dealing with customer, product, or transaction records, exact matching (= operator or JOIN) isn’t enough. That’s where fuzzy matching techniques like Levenshtein distance, SOUNDEX, JARO-WINKLER, or trigram similarity come into play.

Let’s look at some practical applications of SQL fuzzy matching:

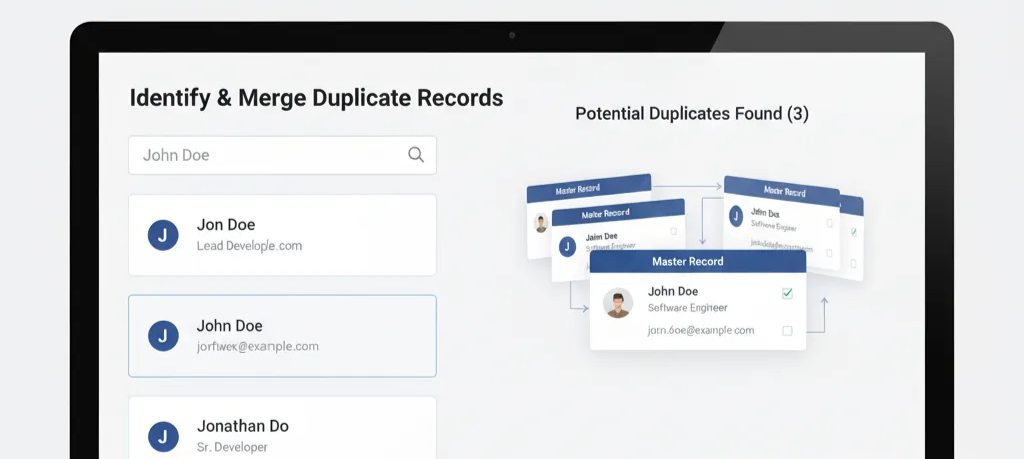

1. Deduplication of Records

One of the biggest headaches in data management is duplicate records. For example, a CRM might contain:

- “John Doe”

- “Jon Doe”

- “Jonathan Do”

These are all different values. But to a fuzzy matching algorithm, the similarity score between these names is high enough to suggest they represent the same person. In SQL, this might be fixed using a JOIN with a similarity function.

2. Handling Name Variations

Names are notoriously inconsistent across systems. Take the example of “Katherine”:

- Stored as Catherine in one table.

- Entered as Kathryn in another.

- Shortened to Kat in customer feedback.

Fuzzy matching can bridge these variations so that when a user queries “Katherine”, the database surfaces “Catherine” and “Kathryn” as well. In SQL, this could leverage SOUNDEX or a Levenshtein threshold.

3. Address Standardization and Matching

Addresses are another common pain point. One customer might list their address as:

- 123 Main Street

- 123 Main St.

- 123 Main Strt, Apt 2

Traditional joins fail here because the text isn’t identical. Fuzzy matching recognizes that these are near-identical strings with only format or abbreviation differences. SQL implementations often use trigram similarity or edit distance to flag near matches.

4. Data Integration Across Systems

When merging data from multiple sources — say, a legacy ERP system and a new CRM — field values rarely align perfectly. Product codes may differ slightly, or company names may be abbreviated in one dataset and spelled out in another.

- International Business Machines vs. IBM

- Procter & Gamble vs. P&G

Fuzzy matching allows SQL queries to link these records despite differences.

5. Fraud and Anomaly Detection

Fraudsters often use slight variations of names, addresses, or emails to evade duplicate detection systems.

- john.doe@gmail.com vs. jon.d0e@gmail.com

- 123 Main Street vs. 123 Mian St.

Fuzzy matching in SQL can flag these near-matches for review.

What are the common algorithms for SQL Fuzzy Matching?

SQL fuzzy matching uses several algorithms to find approximate string matches. They are used for tasks like data cleaning, deduplication (identifying duplicate records with slight variations), and data linkage (joining datasets based on similar, but not identical, identifiers). Here are some of the most common ones:

Levenshtein Distance (Edit Distance)

The Levenshtein Distance, also known as edit distance, measures the minimum number of single-character edits, such as insertions, deletions, or substitutions, required to transform one string into another.

- Purpose: A lower score signifies a higher degree of similarity. For instance, a distance of 0 means the strings are identical.

- Implementation: While not a native SQL function in most standard database systems, it can be implemented using a Stored Procedure, a User-Defined Function (UDF), or through a database extension.

Example:

To transform the string ‘kitten’ into ‘sitting’, the Levenshtein distance is 3:

- k → s (Substitution) →

sitten - Add g (Insertion) →

sitting

SQL Implementation Example (PostgreSQL using fuzzystrmatch extension)

The specific implementation varies by database. This example uses the PostgreSQL fuzzystrmatch extension, which includes the levenshtein() function:

-- 1. Enable the extension (if not already enabled)

CREATE EXTENSION fuzzystrmatch;

-- 2. Calculate the distance between 'kitten' and 'sitting'

SELECT levenshtein('kitten', 'sitting') AS distance_score;

-- Result: 3

-- 3. Find names in a 'Customers' table that are 'close' to 'Jon' (e.g., within an edit distance of 1)

SELECT

customer_id,

customer_name

FROM

Customers

WHERE

levenshtein(customer_name, 'Jon') <= 1;

-- This query would match 'John', 'Jan', 'Jonn', etc., assuming they are in the table.

Soundex & DIFFERENCE (Phonetic Matching)

Soundex is a phonetic algorithm that indexes names by their sound, as pronounced in English. The DIFFERENCE() function in SQL Server compares the Soundex codes of two strings and returns a value from 0 to 4, where a score of 4 means the codes are identical. This is especially useful for finding names that are spelled differently but sound alike (e.g., “Robert” and “Rupert”).

SELECT DIFFERENCE('Robert', 'Rupert'); -- Returns 4

SELECT DIFFERENCE('Robert', 'Richard'); -- Returns 2

Jaro-Winkler (Prefix Sensitivity)

The Jaro-Winkler distance is a measure of similarity between two strings. It’s a variation of the Jaro distance that gives a higher score to strings that have matching characters at the beginning. This makes it particularly effective for data like personal names where prefixes are often correct.

-- 1. Enable the extension (if not already enabled)

CREATE EXTENSION fuzzystrmatch;

-- 2. Compare two names using Jaro-Winkler similarity

SELECT jarowinkler('Robert', 'Rupert') AS similarity_score;

-- Returns: ~0.9 (high similarity; shares several aligned characters and first letter)

SELECT jarowinkler('Robert', 'Richard') AS similarity_score;

-- Returns: ~0.74 (lower similarity; diverges earlier and fewer aligned characters)

- Scores range from 0 (no similarity) to 1 (exact match).

- The algorithm boosts similarity when the prefix matches, which makes it especially useful for names.

Regex-Based Matching (RLIKE, LIKE)

Regular expressions can be used for more flexible pattern matching than the standard LIKE operator. While LIKE uses simple wildcards (% and _), the RLIKE (or REGEXP) operator in some SQL dialects allows for complex pattern definitions, which can be configured to tolerate slight variations.

SELECT * FROM users WHERE name RLIKE 'Jo(h|n) Doe'; -- Matches 'Joh Doe' and 'Jon Doe'

Trigrams (pg_trgm in PostgreSQL)

A trigram is a group of three consecutive characters. The pg_trgm extension in PostgreSQL creates trigrams from strings and calculates similarity based on the number of shared trigrams. This is a highly efficient method for fuzzy searching on large text fields.

CREATE EXTENSION pg_trgm;

SELECT word_a <-> word_b AS distance FROM... -- Calculates the distance between two strings

SQL Fuzzy Matching by Database

While many databases offer different native functions for fuzzy matching, the core principle remains the same: measuring the similarity between strings. The availability and performance of these tools vary by database.

SQL Server

SQL Server has built-in functions for phonetic matching.

SOUNDEX()andDIFFERENCE(): These are the most common tools for fuzzy matching in SQL Server.SOUNDEX()converts a string to a four-character code based on its sound, making it great for finding names that are spelled differently but sound the same (e.g., “Katherine” and “Catherine”). TheDIFFERENCE()function then compares theSOUNDEXcodes of two strings and returns a value from 0 (no match) to 4 (perfect phonetic match).- Edit Distance in Azure SQL: Recent versions of Azure SQL and SQL Server have introduced native or more accessible functions that can handle algorithms like Levenshtein distance, improving the ability to perform more granular, character-level fuzzy matching without custom user-defined functions (UDFs).

PostgreSQL

PostgreSQL’s approach to fuzzy matching is primarily through extensions, which are powerful and highly optimized, i.e., they are designed to automatically minimize the amount of compute resources necessary.

fuzzystrmatch: This extension provides a variety of string similarity and distance functions, includingSOUNDEX()andLevenshtein(). It’s useful for a wide range of fuzzy matching scenarios, especially when you need specific algorithmic control.pg_trgm: This is a very popular and performant extension for fuzzy matching. It creates “trigrams” (three-character groups) from strings and calculates similarity based on the number of shared trigrams. It can be used to create indexes for very fast fuzzy searches, making it ideal for large datasets.

MySQL

MySQL has a more limited set of native (built-in) fuzzy matching functions, so users often rely on other techniques.

LIKEand Regular Expressions: While not “fuzzy” in the true sense,LIKEwith wildcards (%) can find partial matches, and regular expressions (REGEXPorRLIKE) can be used to define more complex patterns that tolerate minor variations. However, these methods are often slow and lack the sophistication of dedicated fuzzy matching algorithms.- User-Defined Functions (UDFs): To get true fuzzy matching in MySQL, developers frequently create their own UDFs, often in a language like C++ or Python. These custom functions can implement algorithms like Levenshtein or Jaro-Winkler to provide more accurate similarity scoring.

Oracle

Oracle provides a dedicated package, UTL_MATCH, for fuzzy matching, which is robust because it offers native, built-in support for multiple, complex algorithms (Levenshtein, Jaro-Winkler) directly within the database engine. This approach is:

- High-Performance: Calculations are done internally in the database, avoiding the overhead of external tools or complex user-defined functions (UDFs) written in procedural languages.

- Standardized: It provides a reliable, supported API that adheres to industry-standard algorithms, ensuring consistent and accurate results.

UTL_MATCH: Oracle’sUTL_MATCHpackage contains functions for calculating string similarity using well-known algorithms. Key functions include:UTL_MATCH.EDIT_DISTANCE(): Returns the Levenshtein distance between two strings.UTL_MATCH.JARO_WINKLER(): Calculates the Jaro-Winkler distance, which is particularly good at matching strings that have similar beginnings.UTL_MATCHfunctions provide both the distance score and a normalized similarity score (from 0 to 100), giving you a clear metric for how close two strings are.

Example Walkthrough: Fuzzy Join on Names & Addresses

Here is a step-by-step example of how to perform a fuzzy join in three different SQL databases: SQL Server, PostgreSQL, and MySQL. We’ll use a scenario where we need to match customer records from two separate tables, with inconsistencies in names and addresses.

The Data

We have two tables: CustomersA and CustomersB. Our goal is to join them on Name and Address to find matching records.

Table 1: CustomersA

| CustomerID | Name | Address |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jane Smith | 123 Main St |

| 2 | John Doe | 456 Oak Ave |

| 3 | Robert Johnson | 789 Elm Road |

Table 2: CustomersB

| OrderID | CustomerName | CustomerAddress |

|---|---|---|

| 101 | Jayne Smyth | 123 Main Street |

| 102 | Jon Doe | 456 Oak Avenue |

| 103 | Bob Johnson | 789 Elm Road |

SQL Server

SQL Server uses the SOUNDEX() and DIFFERENCE() functions for phonetic matching, which are well-suited for names. We will also use a common REPLACE() trick to standardize address abbreviations.

SELECT

A.CustomerID,

A.Name AS CustomerAName,

B.OrderID,

B.CustomerName AS CustomerBName

FROM

CustomersA AS A

JOIN

CustomersB AS B ON

DIFFERENCE(A.Name, B.CustomerName) = 4

AND

REPLACE(REPLACE(A.Address, 'St', 'Street'), 'Ave', 'Avenue') = REPLACE(REPLACE(B.CustomerAddress, 'St', 'Street'), 'Ave', 'Avenue');

Results:

| CustomerID | CustomerAName | OrderID | CustomerBName |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jane Smith | 101 | Jayne Smyth |

| 2 | John Doe | 102 | Jon Doe |

| 3 | Robert Johnson | 103 | Bob Johnson |

Pros/Cons:

- Pros:

SOUNDEX()andDIFFERENCE()are native, simple to use, and perform well for name matching. - Cons:

SOUNDEX()is a phonetic algorithm, so it may not catch non-phonetic typos (e.g., “Maik” vs. “Mike”). Address standardization requires manualREPLACE()functions, which can become unwieldy for many different abbreviations.

PostgreSQL

PostgreSQL relies on extensions like pg_trgm for highly effective fuzzy matching, which we’ll use here to compare both names and addresses.

CREATE EXTENSION IF NOT EXISTS pg_trgm;

SELECT

A.CustomerID,

A.Name AS CustomerAName,

B.OrderID,

B.CustomerName AS CustomerBName

FROM

CustomersA AS A

JOIN

CustomersB AS B ON

similarity(A.Name, B.CustomerName) > 0.6 -- A similarity threshold

AND

similarity(A.Address, B.CustomerAddress) > 0.6;

Results:

| CustomerID | CustomerAName | OrderID | CustomerBName |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jane Smith | 101 | Jayne Smyth |

| 2 | John Doe | 102 | Jon Doe |

| 3 | Robert Johnson | 103 | Bob Johnson |

Pros/Cons:

- Pros:

pg_trgmis extremely fast and effective for both names and addresses. It’s a single, powerful tool for various fuzzy matching needs. The use of a similarity threshold gives you granular control over the “fuzziness.” - Cons: Requires installing an extension, which might not be an option in some restricted environments.

MySQL

MySQL doesn’t have native fuzzy matching functions, so we have to use workarounds like custom functions or more complex LIKE or REGEXP patterns. For this example, we’ll demonstrate a simple cross join with a WHERE clause that uses LOCATE() to find substrings, which can mimic a basic form of fuzzy matching for our simple case.

SELECT

A.CustomerID,

A.Name AS CustomerAName,

B.OrderID,

B.CustomerName AS CustomerBName

FROM

CustomersA AS A

CROSS JOIN

CustomersB AS B

WHERE

LOCATE(SUBSTRING_INDEX(A.Name, ' ', 1), B.CustomerName) > 0 -- Find if first name is a substring

AND

LOCATE(SUBSTRING_INDEX(A.Address, ' ', 2), B.CustomerAddress) > 0;

Results:

| CustomerID | CustomerAName | OrderID | CustomerBName |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jane Smith | 101 | Jayne Smyth |

| 2 | John Doe | 102 | Jon Doe |

Pros/Cons:

- Pros: No extensions or special functions needed. This approach is portable across different MySQL installations.

- Cons: This is an inefficient and unreliable method for true fuzzy matching. It can lead to many false positives (e.g., matching “Robert” with “Roberta”) and won’t catch simple misspellings. It is not recommended for production use.

Comparison of Algorithms for Fuzzy Matching

When working with text data, exact string matches often fall short—especially when you’re dealing with typos, variations in spelling, or names recorded inconsistently across systems. That’s where fuzzy matching algorithms come in.

These techniques help measure similarity between strings and identify matches that aren’t identical but are still close enough to be useful. Depending on your dataset and goals, different approaches shine in different scenarios. Below is a comparison of some of the most commonly used fuzzy matching algorithms, highlighting their strengths, limitations, and best-fit use cases.

| Algorithm | Strengths | Limitations | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Levenshtein | Precise typo handling | Slow on big tables | Deduplication |

| Soundex | Fast, phonetic matches | English-biased, broad | Name normalization |

| Jaro-Winkler | Good for prefixes | Less intuitive | Customer matching |

| Regex/LIKE | Simple pattern search | Not true fuzzy matching | Substring searches |

| pg_trgm | Index-supported, fast | PostgreSQL only | Large datasets |

Choosing the right algorithm ultimately depends on your data size, language considerations, and whether speed, accuracy, or flexibility is your top priority.

What are the performance and limitations of SQL Fuzzy Matching?

SQL fuzzy matching offers a powerful way to handle imperfect data, but it comes with important performance considerations and limitations. The primary challenge is that fuzzy matching is computationally intensive and can be slow on large datasets.

Indexing Strategies

Standard SQL indexes (like B-tree indexes) are not effective for fuzzy matching because they are designed for exact lookups. To improve performance, databases use specialized indexing strategies.

- Trigram Indexes: PostgreSQL’s

pg_trgmextension is a prime example. It creates an index of three-character groups (trigrams) for each string in a column. When a fuzzy search is performed, the database can quickly narrow down the list of potential matches by comparing trigrams, significantly reducing the amount of data it needs to scan. This turns a full table scan into a much faster index scan. - Function-Based Indexes: Some databases allow you to create an index on a function’s output. For example, you could index the

SOUNDEX()code of a column, allowing for fast phonetic searches. However, this is only useful for that specific function and can’t be used for general fuzzy matching.

Without a proper indexing strategy, a fuzzy join on a large table will likely result in a full table scan and a nested loop join, which can be extremely slow and resource-intensive.

Trade-off: Speed vs. Accuracy

A fundamental trade-off exists in all fuzzy matching applications: the balance between speed and accuracy.

- Prioritizing Accuracy: To achieve high accuracy, you may need to use more complex algorithms (like Levenshtein distance) or stricter thresholds. For example, requiring a similarity score of 0.95 will return very close matches, but it may miss valid but more distant matches. This level of accuracy often comes at the cost of performance, as the algorithm needs to perform more calculations on a larger number of comparisons.

- Prioritizing Speed: If performance is critical, you might use a simpler algorithm (like

SOUNDEX) or a less-strict similarity threshold. This can be faster, but it increases the risk of false positives (incorrectly identifying non-matching records) or false negatives (failing to find a true match). For instance, a very low threshold might match “Robert” with “Richard,” which could be an incorrect result.

The choice of algorithm and threshold should be based on the specific use case and data quality. For a critical data deduplication project, accuracy is paramount. For a quick search feature in an application, a slight loss of accuracy might be an acceptable trade-off for a faster user experience.

When to Use Machine Learning for Fuzzy Matching

You can use machine learning for fuzzy matching when you need to handle complex, non-linear relationships and achieve a higher degree of accuracy than traditional rule-based or algorithmic methods. While SQL is great for simple phonetic or character-level matches, ML models can learn from examples to make more intelligent judgments about data similarity.

Machine Learning Libraries

Several Python libraries are designed for advanced fuzzy matching, often building on classic algorithms but optimizing them for performance and usability.

fuzzywuzzy: This library uses the Levenshtein distance to calculate string similarity. It’s easy to use and a great starting point for simple tasks. However, it’s not highly optimized for speed.RapidFuzz: A faster, more modern alternative tofuzzywuzzy. It uses a C++ implementation of various string metrics (like Levenshtein and Jaro-Winkler), making it significantly quicker for large datasets.recordlinkage: This library is specifically designed for record linkage and data deduplication. It provides a full workflow, including blocking (pre-filtering), comparing, and classifying matches using supervised or unsupervised learning models. It’s a more comprehensive solution for complex matching problems.

Hybrid Workflows

The most effective approach often combines the strengths of both SQL and machine learning in a hybrid workflow.

SQL Pre-filtering (Blocking): This is the first and most critical step. Instead of comparing every record to every other record (which is computationally expensive), you use a fast, coarse-grained SQL filter to narrow down the potential matches.

For example, you could use a

LIKEorSOUNDEXquery to only compare records where the first name or zip code is an exact or phonetic match. This drastically reduces the number of comparisons the ML model needs to perform.ML Post-processing: Once you have your reduced set of candidate pairs, you export this data to a programming environment (like Python) and use a machine learning model to make the final determination. The model can be trained on a manually labeled dataset of “match” vs. “non-match” pairs.

It can then consider multiple features simultaneously, such as the Levenshtein distance of the full name, the

SOUNDEXscore of the first name, and the Jaro-Winkler distance of the address. This allows for a more nuanced and accurate decision than what’s possible with a simple SQLJOINcondition.

This hybrid approach leverages SQL’s power for bulk data filtering and machine learning’s ability to handle complex, multi-feature matching, providing a scalable and highly accurate solution.

FAQs on SQL Fuzzy Matching

What is fuzzy matching in SQL?

Fuzzy matching in SQL is the process of finding data records that are approximately but not exactly the same. Instead of a character-for-character match, it looks for similar records, allowing for slight variations like misspellings, typos, or different abbreviations. This is crucial for cleaning data, finding duplicate records, and improving search functionality.

How does fuzzy match work?

Fuzzy matching works by using algorithms to calculate a similarity score between two strings. These algorithms measure the “distance” or number of edits needed to turn one string into another. For a search to be considered a “match,” the similarity score must exceed a predefined threshold. For example, a query might look for all names that have a similarity score of 80% or higher to the name “Jon.”

What is the best algorithm for fuzzy matching?

There isn’t a single “best” algorithm; the ideal choice depends on your data and goal.

- Levenshtein Distance is excellent for finding typos because it measures the number of insertions, deletions, or substitutions.

- Soundex is best for matching names that are spelled differently but sound alike (e.g., “Smyth” and “Smith”).

- Jaro-Winkler is often preferred for matching names or addresses because it gives a higher score to strings that share a common prefix.

- Trigrams are a highly efficient and versatile choice for general-purpose fuzzy matching on large datasets, as they can be indexed for performance.

Can you do fuzzy matching across two columns in SQL?

Yes, you can. You can perform a fuzzy join across multiple columns by combining the conditions in your ON or WHERE clause. For example, you can join two tables on both a fuzzy match of the name and a fuzzy match of the address. The query would look for records where both conditions are met, allowing you to find a high-confidence match across both data points.

Is fuzzy logic the same as fuzzy matching?

No, they are not the same, though they are related concepts. Fuzzy logic is a branch of computer science that deals with degrees of truth rather than absolute true or false values. It’s used in decision-making systems and control systems (e.g., in anti-lock brakes or washing machines). Fuzzy matching is a specific application of fuzzy logic principles to the problem of finding approximate string matches in data.

Summary

Fuzzy matching in SQL is a powerful technique for finding approximate string matches, which is essential for data cleaning, deduplication, and search functionality. It moves beyond exact, character-for-character matching to account for typos, misspellings, and variations in data. For example, applying it alongside query tuning strategies (see our SQL optimizing query with multiple joins guide) can help balance efficiency and accuracy.

Because fuzzy matching can be computationally intensive, performance is significantly improved with specialized indexes, such as trigram indexes in PostgreSQL. Still, there’s a critical trade-off between speed and accuracy—a higher accuracy threshold often requires more complex calculations, which can slow down queries.

Practice Next

Ready to sharpen your SQL skills? Practice with Medium SQL Questions to boost your problem-solving.

Want to drill through applied cases? Check out the Oracle Data Analyst Interview Guide to see how concepts like fuzzy matching appear in real-world scenarios. Pair with our AI Interview Tool to sharpen your storytelling.

Explore more SQL guides to strengthen your foundation: